Roots to Renewal

Roots to Renewal

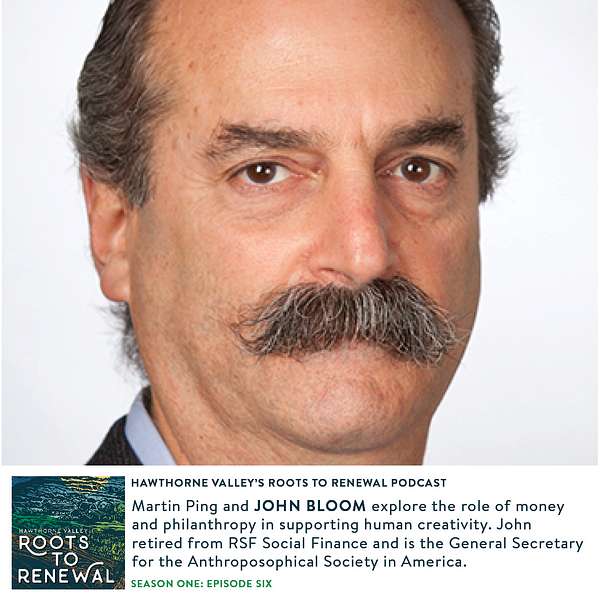

Episode Six: John Bloom on the Role of Money and Philanthropy in Supporting Human Creativity

Sponsored by Tierra Farm | Music by Aaron Dessner

In this episode Hawthorne Valley's Executive Director Martin Ping enjoys a wide ranging conversation with John Bloom, General Secretary of The Anthroposophical Society in America and former Vice President of Organizational Culture at RSF Social Finance, about the role of money and philanthropy in the creative process, and how money can serve human destiny and foster creativity. In the course of their conversation. You'll hear John mention Free Columbia and now independent 501c3 art and social change initiative that was incubated at Hawthorne Valley, and whose pedagogy is inspired by contemplative inquiry, aesthetic education and action research.

Thanks for listening to Hawthorne Valley’s Roots to Renewal podcast. We are an association comprised of a variety of interconnected initiatives that work collectively to meet our mission. You can learn more about our work by visiting our website at hawthornevalley.org.

Hawthorne Valley is a registered 501c3 nonprofit organization, and we rely on the generosity of people like you to make our work a reality. Please consider making a donation to support us today. If you’d like to help us in other ways, please help us spread the word about this podcast by sharing it with your friends, and leaving us a rating and review.

If you'd like to follow the goings-on at the farm and our initiatives, follow us on Instagram!

Heather Gibbons (00:15):

I'm Heather Gibbons, and this is Hawthorne Valley's 50th anniversary podcast Roots to Renewal. Thank you for joining us. This episode marks six months of conversations designed to help mark this significant milestone in Hawthorne Valley's journey. And so far we've enjoyed sharing the stories of our friends and contemporaries folks from around the world who dedicate their lives to meeting the ecological, social, and spiritual needs of our time. As we head into the next six months, you'll be hearing more voices from within our organization as well. Roots to Renewal is made possible by the generous support of Tierra Farm, a family-owned environmentally conscious manufacturer and distributor of organic dried fruits and nuts. Learn more at https://tierrafarm.org. Since 2016, John Bloom has been the general secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in America. He serves as a spokesperson for the society and country representative in the international movement. He also served for more than 20 years as vice president for organizational culture of RSF Social Finance in San Francisco, retiring at the end of 2020. As part of his work at RSF, John developed and facilitated conversations and programs that address the intersection of money and spirit and personal and social transformation.

Heather Gibbons (01:29):

He wrote frequently for RSF Reimagining Money blog and has fostered collaborative dialogues on the challenging social aspects of money. As part of his work, he has helped developed awareness of issues surrounding land and biodynamic agriculture across the US. He has written extensively on many aspects of charitable organizations, associative economics and the topics of money and philanthropy, including the books, The Genius of Money: Essays and Interviews Re-Imagining the Financial World and Inhabiting Interdependence: Being in the Next Economy. John lives in San Francisco. Our executive director, Martin Ping enjoyed a wide range of conversation with John about the role of money and philanthropy in the creative process and how many can serve human destiny and foster creativity. In the course of their conversation, you'll hear John mention Free Columbia, a now independent 501 C3 art and social change initiative that was incubated at Hawthorne Valley, and whose pedagogy is inspired by contemplative inquiry, aesthetic education and action research.

Martin Ping (02:32):

The listener will not be able to see what I see, which is a beautiful work of art behind you. And it's one of your works of art. And for the people in my life, the people who have been my awakeners and my inspire-ers, many of them began as artists and then moved into law or some other field, I think on that a lot. And I think that your book, The Genius of Money: Essays and Interviews, Re-imagining the Financial World, you actually explore this cultural story of money by looking at works of art. I wonder if you could say more about the connection between money and art and the creative process.

John Bloom (03:10):

Maybe I can start by saying why I chose to use the history of art and works of art as a kind of reflection space, contemplation space in understanding money. And part of it is that art actually, aside from the beauty and all the rest that came with, that was also one of the primary tools of educating and building culture. So the messages that were in those works of art were hugely important. If you don't think that's true, you might want to ask why the church was so interested in having some of the great masters of the Renaissance paintings, right? So there was a lot of teaching in there. So I really want to say, so how hard it's dealt with this question of money and what messages were they working with and putting out into the world that people would learn from - what kind of judgment was there.

John Bloom (04:05):

So, you know, you have Jotto painting, you know, Lucifer or ahriman or the devil. However you want to interpret that, you know, with the money bag, right behind Judas in the, in a painting in the Scrovegni Chapel. Well, that is a pretty powerful statement about money as a visual image. And those visual images are, I mean, those are powerful. They stick with us, right? So, you know, anytime anybody has a quote bag of money or an offer for me, even when I get the mail with a credit card offer, I have this sense that there's someone behind me with a little bag making an offer I can't refuse. And that's an image. So it is a powerful archetypical kind of picture. So I really wanted to explore, well, how has culture generally, of course, I can't speak for all of culture. I can only speak for myself around that, but how have we digested these images and how have they played out in our lives and had meaning in our lives and influence how we see the world in our, the money world.

John Bloom (05:07):

So it actually pretty much scans the history of art to some degree. And every piece always opened up something for me that I had never imagined an artists would have been thinking about or connected to, or something about the culture that was a reference from that time that, that conveyed attitudes about money. So it just was a huge exploration, both from my own study of the history of art, which I did as a painter and as a semi art historian, certainly a photo historian and understanding how to look into a work of art. But then when it's the cultural messaging, I think of John Berger and all the development of meaning, what is it that's living in our culture as archetypal pictures, that's influencing even day to day transactions that we need to bring into in a way, and we're have received those messages because you know, those paintings don't get us into the whole realm of media and the realm of commerce and advertising, which is also an off-stream of artistic activity, which is also about messaging and convening of values. And maybe not as innocent as some of the early paintings, but until we understand that there's a whole history of messaging in the art, even as removed and inspired by it, you know, I think we, we miss a piece of what's made current economic life possible, and what's actually alive that we're part of some, you know, unfolding drama. That's not going to stop with us and preceded us.

Martin Ping (06:41):

And it's interesting, just hearing that to think about the difference between how many people were viewing those paintings when they were first created. Now over time, certainly more and more people have had the opportunity to see them, but the difference between that and nowadays where an image can be produced and beamed around the world like that and for, you know, for good use or not, it makes me think of Edward Bernays and kind of the father of propaganda, I guess you would say, who was the nephew of Sigmund Freud? He saw early on the opportunity of the power of image to influence our behavior. And boy that one's been playing out.

John Bloom (07:20):

I mean, this is something I quoted fairly often, but it's so significant 1955 Art Directors Annual. So that was a big magazine that was put out for all the advertising agents. And this is a direct quote from them. It is now the business of advertising to manufacture customers in the comforts of their own home. Been pretty successful, no, 1955 that's a lot of years ago. And so that has been a primary motivator to basically manufacturing customers. They said, customers, you know, we call them consumers now. So in a way that's treating the human being, who's receiving that message as a commodity. That is not what I would call ennobling the human being ultimately education, which is an art itself and the arts, the actual production of, you know, visual and performing arts need gift support. And so if one looks from an associative economic standpoint at the flow of money, and it's multiple forms, if actual all that surplus, which of course is meets needs, and, you know, should accrue to a reasonable degree so that people can retire, you know, take care of themselves.

John Bloom (08:34):

And that's not the point, but how much over accumulation do we need? So how much should we go beyond what is actually what I call Hmm, sufficient, could we look at sufficiency? And, you know, each person is going to have a different view of that, but instead of all of that capital, which is being extracted out of the system and coming into private ownership and private use, and then gets developed into investments and derivatives and hedge funds, and just continues to kind of circulate on making its own money - making money, make money, if that were actually some of that were rightfully turned back into culture to renew the culture. This is the regenerative, this is the reciprocity picture. Then we could actually have artists working out more of a gift stream, which is what Free Columbia is really trying to do. Link the freedom that comes with that gift stream, as opposed to the strings attached, or I'm going to contract with you to make a painting, which, you know, that happens too.

John Bloom (09:33):

But how do you actually free up the exploration that an artist needs to take to know out of chaos can come order. To me if I really think about the creative process, which of course, if you're involved in the arts, that's when you're in, in a way it doesn't flow well out of fear. Flows out of trust. If you're operating in fear, you might problem solve out of fear, not necessarily the best way to problem solve. That is only a small fragment of the true creative field. So problem-solving is creativity, no question about it, but it's only a small portion of it. That is a very reactive modality of creativity, but what if there's nothing to react to? And you're actually just trying to bring something out of nothing in a way it's not really out of nothing, but let's use it in that way.

John Bloom (10:24):

That's sometimes a scary place to be. I know, you know, if you're staring at a blank canvas or white sheet of paper and say, okay, I can do anything. What happened? What do I do? So the beautiful part of that is the capacity to know you just go for it. And if worst comes to worst, you paint it over and start again. And if it gets even worse, you paint it over and start again. So there's an ability to move to a place of trust that is in service to something moving through that. And you have to recognize when that's working and when it's not, but that is the epitome of inefficiency. Economics hates inefficiency. If you really think about it, everything in economics, in market economics anyway, is geared toward how do we make it more productive? So we'll reduce everything to commodities because it's more efficient. And the creative processes are intentionally completely inefficient. Not that they're not productive and innovations and breakthroughs come in that space, but you cannot link efficiency in innovation. Not really. So the real question is how do we free up capital that frees up, not the work, but the time where all of the, that chaos can happen and all of that creativity can happen and failures can happen. We're so outcomes based, we can't handle the notion of failure, but that's where we all learn.

Martin Ping (11:42):

I don't know how true it was, but I once heard that Edison was asked about his 15,000 light bulbs that didn't work as if they were failures. And, and he said, no, I just discovered 15,000 ways not to make a light bulb.

John Bloom (11:59):

And by the way, would you please share that with others? So they also don't make the same mistakes.

Martin Ping (12:14):

Most of the years, that I've known you have been through our long association with what was first called Rudolph Steiner Foundation, and then became RSF Social Finance. You just very recently ended your very impressive tenure with RSF, which was how many years,

John Bloom (12:35):

Almost 23 years.

Martin Ping (12:35):

23 years. I was wondering if you could describe the mission of RSF, social finance, and maybe say a little bit about your role within RSF.

John Bloom (12:44):

I would say about RSF Social Finance, so it was actually founded first foremost, out of a study of Rudolf Steiner's economics lectures. So almost everything that was put in place as practices in early years of Steiner foundation came from aspects of those lectures practices around associative economics practices around lending. How to think about lending, how to build community and the nature of economic communities. And then also the question of how money serves human destiny. And I think that that question was at the core of some of the founding principles and of course, meeting practical needs in the world - hugely important. And it really was an expression of the spirit is never without matter and matters, never without spirit in the sense that one actually had to work in the material world, but with what attitude, how could one actually come to that place? So that was, I would say some of the core founding ideals, but my work really was in building the culture of the organization as a organization that values, reflection, values, learning and growth, and the development of every individual in the organization as a kind of path where, you know, we're doing that, sharing that together.

John Bloom (14:06):

And sometimes that works for a long time. And sometimes it's a short period of time. That is not the point where it's the fundamental, how is it nourishing people who are coming to work there so that they feel like they're growing and changing and have opportunities and a role that was where I showed up in many ways, even though of course, busy supporting lots of projects and kind of doing that same work, but in other organizations and helping them along. So it's all, you know, learning process because one always informs the other. So it's a long arc. Wasn't always easy. And in some ways like any culture has its ups and its downs. I really see it as really the closest parallel I can come up with is yogurt culture, which I know is quite central to Hawthorne Valley as well. So, you know, without your culture, you're in really big drop off, but you probably have no idea.

John Bloom (14:58):

So I'm just gonna use this as a parallel example. You probably have no idea how many people have taken Hawthorne Valley yogurt and started their own personal yogurt culture with the Hawthorne Valley yogurt. Right. Right. You haven't probably ever thought of that.

Martin Ping (15:12):

No shocking.

John Bloom (15:13):

Right. So, so you right away, you can go say, wait, wait, product control. And you say, no, no gift to the cosmos. Right? It's actually the seed that makes many other things possible. So in some ways I've really seen the culture building like that. And when somebody has left RSF or gone someplace else that they take that with them and try to bring that into wherever they are going next. Right. And colleagues have said, you know, I love the work that I'm doing now, but I really miss the culture that everybody in an organization actually feels seen and paid attention to for who they are, not just what they're doing.

John Bloom (15:52):

Can you produce more? No, that's not the point at all. Like, who are you? And how are you showing up every day? And what are your challenges? And for me, the, the key to associated economics is what is the purpose of economic life? The purpose of economic life is actually this support human beings, being able to survive together on the earth and that the earth actually surviving the human beings, working with it in relationships. So ultimately economics is about the material life and how we meet needs and our needs are met. That's really the essence of it. I I've sort of boil it down to the simple statement of unused resources with unmet needs. And when you begin to match unused resources on unmet needs, you get economic life. That's, that's how it, that's how it surfaces. So if you hold the sort of human being at the center of it, then that's part one part, two of it is that you really have to look at the nature of gift as the whole foundation of all economic life.

John Bloom (16:59):

And that's not what you will find in any economics textbook anywhere, right? It just doesn't exist in an economic sector. You might get philanthropy, oh, you get to do philanthropy after you've, you know, basically extracted millions of dollars from the system. Then you get to give it back, right? Maybe that's one rather editorialized view of philanthropy. And it's not at all, always like that. I just exaggerate on purpose. But the fact is, when you look at natural resources, you look at the land, you look at the forest, the sky, the air, but they all preexisted us in a way, and they're not economic. They came as gift to us. And if we've received them as gift, then we start to work on where we bring our capacities. So capacities are also gifts, right? So that nothing is economic until it begins to come into, into the practical and an, a production.

John Bloom (17:51):

So every human being has different capacities and those are each person we call them gifts, right? Oh, what gifts does that person bring? Right? Current parlance is, oh, that's my superpower, which is intriguing to me. But I, you know, we all have gifts that we bring to the world, but we all have something that we showed up in the earth to do on behalf of humanity. So that's also gift. And then this question of capital, which most, everybody confuses with money. It's not money, right? For me, the definition of capital is how spirit, how intellect, how inspiration shows up in the practical world, in the economic life. That's what capital is. So the fact that we have ideas, those are resources. We have an infinite number of infinite amount of capital around us that we can then bring in service. So that is also a gift.

John Bloom (18:44):

Nobody manufactured that, right? So we have the three basic elements of economic life, which when they start to come in relationship to each other, you get associative economic activity. But if you understand that it all started in gift, then there's a certain humility that comes in that that says, oh, we can't keep extracting without giving back. Because gift is a kind of a reciprocity process where you receive something and you give, you receive your gift without giving and receiving no reciprocity. This is really no gift. You know, giving a gift to someone to no receiver makes no sense whatsoever. And in fact, it isn't really a gift until it gets there, right? So that's such a profoundly different view of our relationship to the world that has to be under underpin all of us associative economic activity. Then we can look at money differently in relation to capital in our inner life and are in a sense, our behavior around money, the notion of reputation, how we come together, how we set price, all those things change when first of all, we're all operating in gift. And second of all, it's all about people and people make up the economy. So it really isn't until you get natural resources turned into commodities and labor turned into commodities and capital turned into a commodity. In other words, using, you know, capital to make more capital that they disconnect from human productivity and start this kind of turn into something themselves, which you know, is an extractive economy. It's a thing based economy, product based economy. It's not a human based economy.

Martin Ping (20:27):

I would encourage anyone listening to this podcast and that they read your book, Inhabiting Interdependence, Being in the Next Economy. I love the title. It's for me, the title itself is a meditation because it really moves beyond just epistemology into an actual ontology of how we are in the world and how we experience what you're just describing, which is that standing behind all this economic activity is the gift that it's all based in the gift. And if we can really live into that, we begin to find our way back into relationships or forward into relationships in a new and a new way. And I think a transformative way. Thank you, John. We've all benefited from your wisdom and your humor over all these years. And I, I just want to thank you for that and thank you very much for today as well.

Heather Gibbons (21:24):

If you're interested in hearing more from John, he regularly shares musings on a variety of topics in his, From The General Secretary posts on the Anthroposophical Society in America's website, his books, the genius of money and inhabiting interdependence are available at Steiner books. Their web address is https://steinerbooks.presswarehouse.com. Thanks for listening to Hawthorne Valley's Roots to Renewal podcast. We are an association comprised of a variety of interconnected initiatives that work collectively to meet our mission. You can learn more about our work by visiting our website https://hawthornevalley.org. Hawthorne Valley is a registered 5 0 1 C3 nonprofit organization and we rely on the generosity of people like you to make our work a reality. Special thanks to our sponsor Tierra Farm, without whom this podcast would not be possible. We're so grateful for their continued support and the support of grassroots contributions from our listeners. To make a donation visit https://hawthornevalley.org/donate.

Heather Gibbons (22:27):

If you'd like to support us in other ways, consider sharing this episode through social media or leaving us a review wherever you listen to this podcast, thank you to Grammy award-winning artist, Aaron Dessner for providing our soundtrack and to Aaron Ping for his editing expertise. Join us next time for part two of our conversation with Francis Moore Lappé, as we help celebrate the release of the 50th anniversary edition of her bestselling book Diet for a Small Planet in September. And in October, we’ll share a conversation with accomplished artist, arts educator, and the co-founder of Light Forms Art Center in Hudson, New York, Martina Müller.