Roots to Renewal

Roots to Renewal

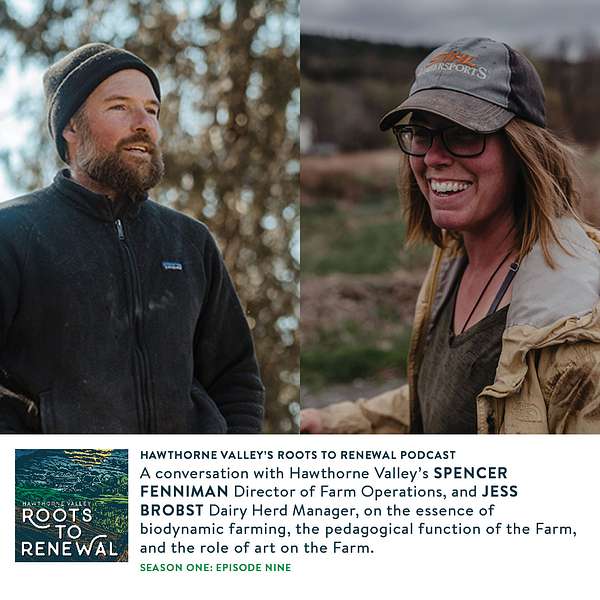

Episode Nine: The Art of Farming with Hawthorne Valley's Spencer Fenniman and Jess Brobst

Sponsored by Tierra Farm; Music by Aaron Dessner

In this episode, we stayed in our own back yard – right here on Hawthorne Valley’s 900-acre Biodynamic farm. Hawthorne Valley’s Executive Director Martin Ping sat down with Spencer Fenniman, Director of Farm Operations, and Jess Brobst, our Dairy Herd Manager. Together they discuss the essence of biodynamic farming, the pedagogical function of the Farm, and the role of art on the Farm.

We are very excited to share this behind the scenes glimpse and for you to hear firsthand the intentionality and profound thought that goes into biodynamic farming. We are grateful to Spencer and Jess for taking time out of their long and incredibly busy days to share their perspectives, and are filled with gratitude for their many contributions to Hawthorne Valley.

Spencer Fenniman (he/him) is the Farming Director at Hawthorne Valley Farm. He has managed fields and fertility at Hawthorne Valley since arriving in 2012. As a younger person, his studies in Anthropology, food geography, and something-useful-to-do-outside-ski-season led him to a series of organic and biodynamic farming apprenticeships. The more he practices nature-based farming, the more he appreciates the land and the deep knowledge, listening, creativity and dedication of his agricultural teachers. For Spencer, biodynamic farming is a way of life based in connection, and managing the soil, the livestock and the ecology in a holistic manner provides the fertile grounds for personal, productive and pedagogical connection. He lives in sight of the farm with his wife and 2 children.

Jess Brobst Hawthorne Valley Farm as a whole farm apprentice in 2016 before moving up the ranks to herd manager in 2018. Jess grew up on a farm in West Virginia and comes with a lot of experience working with animals. She has an extraordinary work ethic and has an amazing way with cows. When she isn’t working on the farm with the dairy herd, Jess is at home making beautiful artwork, studying Waldorf pedagogy through Hawthorne Valley’s Alkion program or walking with her dogs, Nina and Josie.

Visit the farm's website.

Donate to Hawthorne Valley.

Thanks for listening to Hawthorne Valley’s Roots to Renewal podcast. We are an association comprised of a variety of interconnected initiatives that work collectively to meet our mission. You can learn more about our work by visiting our website at hawthornevalley.org.

Hawthorne Valley is a registered 501c3 nonprofit organization, and we rely on the generosity of people like you to make our work a reality. Please consider making a donation to support us today. If you’d like to help us in other ways, please help us spread the word about this podcast by sharing it with your friends, and leaving us a rating and review.

If you'd like to follow the goings-on at the farm and our initiatives, follow us on Instagram!

Heather Gibbons (00:08):

Hello, I'm Heather Gibbons and this is Hawthorne Valley's 50th anniversary podcast, Roots to Renewal. Roots to Renewal is made possible by the generous support of Tierra Farm, a family owned environmentally conscious manufacturer and distributor of organic dried fruits and nuts. Learn more at tierrafarm.org. If you have been a regular listener to our podcast, we thank you for your support. If you are new to this podcast, welcome, we are so happy you are here. We started Roots to Renewal to share Hawthorne Valley's story and engage in conversation with friends from around the world who dedicate their lives to meeting the ecological, social, and spiritual needs of our time. In this episode, we stayed in our own backyard right here on Hawthorne Valley's 900-acre Biodynamic farm. Hawthorne Valley's Executive Director, Martin Ping, sat down with Spencer Fenniman, Director of Farm Operations, and Jess Brobst, our Dairy Herd Manager. Together, they discuss the essence of Biodynamic farming, the pedagogical function of the farm and the role of art on the farm. We are very excited to share this behind-the-scenes glimpse and for you to hear firsthand the intentionality and profound thought that goes into Biodynamic farming. We are grateful to Spencer and Jess for taking time out of their long and incredibly busy days to share their perspectives and we are filled with gratitude for their many contributions to Hawthorne Valley.

Martin Ping (01:31):

Good morning, Jess and Spencer. We're going to speak about agriculture and farming, and I'm curious just right out of the gate, if you would be able to say what attracted you to farming in the first place.

Jess Brobst (01:45):

Wow. This is a great question to which I have a very long answer, so I will try. As a child growing up in West Virginia, when I thought of farming, I saw soybean fields or corn fields or thought of FFA and those kinds of worlds of agriculture. And the idea of these kind of diversified small-scale, organic, Biodynamic, educational, I didn't even really realize that existed. It wasn't even on my radar. I was pretty naïve or ignorant of that kind of agriculture. And so the agriculture I knew from back in rural West Virginia didn't appeal to me at all. It wasn't even something I considered. And so I was interested in animals and art and all sorts of other things. Spent most of my working life working in kennels as like a dog assistant in veterinary clinics, grooming facilities, because that's how I thought I could work with animals.

Jess Brobst (02:37):

After several years of doing that, I just got really run down of that kind of an environment and just really wanted something different. I was looking actually on Craigslist and came across an advertisement for an organic farm, an organic vegetable farm, on the Maryland/West Virginia border that was looking for a farm hand. And basically the advertisement was written in such a way where it was saying things like, "Do you want to work with your hands? Do you want to know where your food comes from? Do you want to feel like what you do matters? And that you're connected?" And I was like, what is this place, what is this magic place? Yes, that's what I want to do. And I didn't even know that's what I wanted to do, but when I read those words something kind of stirred in my heart. And so I applied and so I was used to bustling around doing work and I fit right in on a vegetable farm in that capacity.

Jess Brobst (03:28):

And so I took to the work itself very quickly and just the other things started to open up, just this awareness of how much these kinds of relationships matter, how much the food matters. And so after kind of working there for two seasons, I decided I really wanted to know more and I wanted to pursue an apprenticeship. And so that's how I came to Hawthorne Valley. I saw an advertisement on an apprentice search engine that was spotlighting Hawthorne Valley Farm and when I saw the website that had the art and the children and the animals and all of these things that I had loved my whole life, and then these new loves that I was finding. Once again, I was like, what is this magic place? I have to go there. And it was the only place I applied to because it's the only place I wanted to go to. And I was accepted and here I am almost five years later.

Spencer Fenniman (04:24):

Yeah. I did not grow up into it. I just completed college with a degree in Anthropology, focusing a lot on rural communities and mostly in South America. I decided to take some time off from that while I was pursuing what to do next and was really just skiing and working as a dishwasher and not really going anywhere with that. I felt like I wanted to develop life tools and really figure out how to survive on the planet. And that I think just drew me to a farm opportunity and this was up in Northern Montana and I felt like I just kind of slid into the lifestyle. There was this real gratifying work. I wasn't really getting paid, but that wasn't the point. I think the first sale of produce to a customer really was part of it and then part of it was being out, working in a field and listening to Sandhill Cranes.

Spencer Fenniman (05:18):

So I suddenly found myself going to another farm and starting to work and then that was when I first started working with livestock and sheep in Maine. There was something that really clicked there. I think working with this tapestry of landscape of pastures and fields and it was a more complicated farm and suddenly that really got into the logistics aspect of it. That was something that really clicked with myself and moved out to Oregon and was drawn to the idea of Biodynamic through that work with livestock, through that work with a mixed farming aspect with a farm that had this deep attention to more than just the farm, towards all that encompasses the farm habitat. Now, it's been I think 15 years, 16 years, and I am continued to be in this lifestyle and, and really can't think of another way. It's a beautiful thing. When I got to Hawthorne Valley, I think the first thing that inspired me the most was, there used to be these fish tanks in the Farm Store. And I met Conrad coming out with buckets of stream water to fill into the fish tanks in the Farm Store. And aside from everything else that was going on, which it was, there was a lot of vibrancy, I think that that particular moment really struck a strong chord.

Martin Ping (06:39):

That's great and making me just smile so broadly to think about the Farmscape Ecology Program corner in the store when we first opened the store in its current location and Conrad with buckets of stream water. It's a beautiful image. You mentioned Spencer, you used the term lifestyle and I often think that you know, we're hopefully as a school, we're educating young people more for, not so much to get a job, but more for hearing their own inner voice. What are they being called to do in this term vocation? And it seems of all of the things that people can do, farming feels to me almost more like it calls you more than you call it because if you sat down and logically thought about it and many people would run the other way and you and I spoke recently with the challenges that we're seeing with way too much rainfall and the east and not enough rainfall in the west.

Martin Ping (07:40):

And it's almost a miracle that farmers just don't throw in the towel and one gets a sense well, almost, maybe you can't because you're just feeling called to do it. And it is so essential that people are doing it so we all can eat. Thank you for answering the call, if that is in fact, at all an accurate portrayal. You also use the term biodynamic and Hawthorne Valley is a [Demeter certified] Biodynamic farm. And you began to hint what that might mean. I wonder if you would be able to elaborate Spencer, a little bit further on how you might describe a Biodynamic farm or what biodynamics mean to somebody who has never heard of it and is asking you for the first time.

Spencer Fenniman (08:29):

I think that the place that I would always start in describing that is through this cultivation of the farm organism. And if we think of the farms are this kind of locus of strong human intention, where we're putting a lot into creating a certain landscape that's providing for a whole host of relationships. For the animals that graze the land that eat food from the land, for the humans that eat the food that's provided for the farm, for the trees that provide habitat and for the wild areas that exist on the edges, there's all these nested relationships that we're creating. And what I think is really brilliant about biodynamics is that it's based on this openness to look beyond just the material relationships. It's based on this willingness to consider relationships that might not initially be apparent. And whether that is from the movement of the stars and their effect on plant growth, to what the insects and birds that live on the fringes of your farm are bringing, or even to how we can enter into a relationship. For instance, that's happening into the compost pile beyond just mechanically and influence the end result. Results probably not the best word, but influence the outcome that's emerging from that relationship.

Martin Ping (10:00):

That is, I think, a beautiful introductory and beyond. I mean, that goes really quite deep into these relationships and really presents such a beautiful image and picture to work from. I wonder, Jess, if you had anything else you might want to add to that.

Jess Brobst (10:17):

I like to think of it as the whole farm individuality, but yeah, organism. This idea that we're working in this being in and of itself, which in some ways I have a tendency to personify it in my mind when I think. If I think of somebody I love like my mother or a sister or something and how much care and attention I want to spend on that person, how I want to get to know that person, how I want to help that person live a balanced life. I think about that with the farm as well. It's how can I get to know this place and listen to what it's telling me so that I'm not walking up to it and just trying to impose my will, or my limited perspective on this farm, but actually see what it has to say, which isn't in human language.

Jess Brobst (11:03):

So you have to be aware, you have to be observant, you have to be quiet. So it becomes an inner practice of how you present yourself to the farm and how you pay attention to the farm and all of these places like he was saying with how we interact with nature, how the pieces itself interact, and then also just the human element to me is so important. As humans, we have a tendency to remove ourselves from nature when we're looking at nature and probably as modern farmers, we do that as well, but our sustainability, our wellness, our balancedness is just as important as the farm. And so for me, that means living a diversified life, just like I want to bring diversity to my farm. So I don't want to spend an entire day doing one task or I don't want to limit myself to just one area. I need balance just as much as anything else. And so how can we create sustainable, beautiful lives for our workers and ourselves as well as the animals and the plants that we're working with.

Martin Ping (12:06):

That fills out the image in a very beautiful way. And one thing I heard you say in there is listening, that you go out to listen, what is it that the farm needs and what a different picture that is than just going out and saying, let's impose our will on this land or on anything and just have the result as Spencer said, be something that's so human directed without that listening first. I think that's so important. It makes me think of the relationship between humus, human and humility. It's just beautiful imagery that you've created there. You also threw out the term sustainable. And that's a term that has been widely kicked about for awhile and seems to have morphed, in more recent years, into this term regenerative. We have all these descriptors for ways that people are trying to explain how they farm. And then there's some criticism around that, that actually we're coming up with these terms for millennia. There were cultures who were practicing this type of agriculture or having this more sensitive listening relationship to the land. And I wonder if you could say something to that and maybe we'll start with you Jess, on that one.

Jess Brobst (13:24):

This is something I won't pretend to be an expert in, or to be aware of the social movements moving around and the awarenesses that are dawning. It's like, I sort of know my life and what I'm doing, but yeah, I think that's another thing humans have a tendency to do and we were talking about that earlier. But we like to think we just found something or we just made something up. And there's a verse in the scriptures, the old Testament, that I enjoy where it's like, there's nothing new under the sun. Nothing is really new. Everything has always been. And just because we found our way into relationship with something doesn't mean, we are the discoverers of that relationship. Some of these original peoples that had these relationships, they had this way of connecting. They were reading the landscape and that's why they were doing practices that were so healthy and balanced.

Jess Brobst (14:17):

And so they had a direct relationship with the land and could thus, work accordingly. And as time has gone on, it seems that humankind has either lost that relationship or severely damaged it based on some of the things that we've been doing to the land and ourselves. And so, to me, it's amazing if we feel like we're finding our way back to listening, but we are not the first people to listen, even if we ourselves are just now learning to listen. So, never feeling like we're claiming something or just being thankful that we found ourselves in a place where we've been able to get out of that modern mindset of selfishness or whatever, and just be so thankful that the earth is willing to let us listen to her or something. I don't know if I know how to say that really eloquently. Maybe it is like a case for reparations just saying, hey, I recognize this, this is important, but I've also recognized where other cultures knew this was important. So maybe we need to make some kinds of statements, these relationships aren't new, but then maybe we'll just get to a place where it is the new normal that everyone has a relationship to the land. I don't know if I'm saying this well enough, but yeah, something like that.

Martin Ping (15:32):

Spencer to you also that, I think in a way I think of this, we're trying to find our way into a narrative that people connect to bring agriculture into the future. And yet it is true that so much of it is actually already embedded in our collective past. And how you think about that?

Spencer Fenniman (15:53):

I think that the past century and a half is kind of unprecedented in human history, movement of people away from the land. With that has come a demand on agriculture to provide or a greater percentage of the population than previously was. And I think that informs a lot of the narratives that we use now. Something that I think about a lot is the process by which people become indigenous to a place. Jess spoke about listening and obviously there's a patience that comes with how the responses of a landscape or an ecosystem to kind of, emerge into adaptive process. I think that terms like regenerative or sustainable, there's never a blueprint. They're always going to emerge out of the specific context by which they're being practiced. The thread that's continuing with all of them is to look at how can we produce food in a landscape, ultimately, what can we produce in a landscape?

Spencer Fenniman (16:55):

And if that's not food, is there something else that can be produced outside of the economic material food production? There's lots of other things that landscapes can provide. Expanding the definition of what we're providing and by listening to the land is part of this new narrative that's required. I think that there's instances of lands that have stopped being productive farmland and become productive ecosystem habitat. I would say another component is that as we've shifted more towards an urban society, that there's this desire to then shift land into either, well, this is where productive farms exist and this is where non-productive farms are going to just disappear. Whenever we centralize, we're not as strong as when we have things more decentralized. And the economic pressures that lead to this centralized food production system, I think is not the answer towards a broader regenerative food system.

Martin Ping (17:58):

I have to say, I would agree with you there. I also hear you speaking about the other roles that farms can play and not the least of which is just that they do provide an opportunity for people to ponder these questions and connect to nature in a different way than they may in their own surrounds. And that leads me to Hawthorne Valley Farm, specifically, which is part of this larger association, Hawthorne Valley Association, which is a wide raging set of initiatives, including production, retail, education, research, art. And so one of those functions that our farm certainly plays is a pedagogical function and that goes to the farmer training programs and also to the visiting schools coming to be on the farm, our own school, Hawthorne Valley Waldorf School, on the farm. And I wonder how you both think about, are there more educational opportunities that you would like to see manifest in this organism called Hawthorne Valley Association? Jess, this is a conversation you and I have frequently and I'm just wondering if you could share a little bit about your visions for the pedagogical function of the farm.

Jess Brobst (19:16):

Yeah, it's like literally one of my favorite subjects. I am very passionate about the apprenticeship program and learning in general. I started as an apprentice and I experienced certain things as an apprentice that I'm like, man, I'd love to make this different, I can really see where this maybe isn't so helpful, or this needs to grow. And I've been able to experience how my efforts have made changes to the apprenticeship program and I'm capable, how, we're so capable of making change when we're really passionate about something as human beings. And so I think this place really supports people being able to bring things into existence that I feel like that's how all these initiatives have come forth, that somebody has had a dream or a vision and has been able to give it life. And so we've talked before about this idea, this kind of academy, or this thing that could help unite and organize all the different learning roles that take place at the Association, whether it be the apprentice program on the Farm, the internship program with Farmscape Ecology, even the Alkion students in the Waldorf teacher training, or even just teachers in general, maybe their assistants.

Jess Brobst (20:32):

Somebody that is still learning from the head teachers like how to go about doing their tasks. There's all of these roles, Place Corps, VSP. This touches on what I mentioned before about really requiring diversity, not just in our farms, but within ourselves. And I know I get so much as a human being, from interacting with these different areas. I'm an Alkion student, I work with the VSP, I've been working with Farmscape Ecology and it really brings so much to me. And so what would it look like to have a program that could weave into all of these things while at the same time, not overwhelming a student with too much at any given time, because I think it is important to be able to focus in one area to get a good foundation, just how can we tap into what is already here and maybe make it stronger or more connected. We shouldn't underestimate these microcosmic moments to bring unity and cross collaboration, but then how can we also devise systems to bring them together?

Spencer Fenniman (21:36):

Yeah, I would say my path was more from a foundation in agriculture and I still think that foundation in agriculture provides a wonderful springboard towards engaging with so much more. I think our apprenticeship is always striving towards doing that while maintaining that fundamental approach towards agriculture. Beyond just our specific pedagogical programs, I think the farm should always have the most willingness to allow the public to engage with the production or the landscape, because I think there is so much to be gained. And I think one of the tragedies of the last year and a half has just been that absence of the public having this nose to nose interaction with a pig, or being able to cautiously reach out and stroke a cow. I see this potential always for having more access towards that on our farm, because I think in those interactions comes learning and it might not just be an academic or even an in-depth learning, but it might be a spark towards perhaps a more empathetic relationship with animals or a different viewpoint on even something as simple as a stream.

Martin Ping (23:02):

I really love, Spencer, that you said there is foundational learning that can happen through the apprenticeship program that can be become informative regardless of the ultimate life path they take, that there's just something for later on in life. We're farming in a time and we're trying to live our lives in a time where the planet is rapidly changing around us. And we've experienced it in one way here at Hawthorne Valley with these crazy rain events and 14 inches of rain in July and multiple floods and as we say, other places are experiencing it the opposite. And the question is, how can we be educating towards a greater resilience for the future? And that's, I think speaking both to outer resilience and inner resilience, and I'm sure you are both thinking about that.

Spencer Fenniman (23:55):

The margin of error and what we do is that much smaller every year. And I think on the one hand that is daunting, but on the other is really clarifying. Clarity is really usually the first step towards becoming adaptable. And that's kind of an internal clarity. This path towards inner resiliency in agriculture is something that's very challenging. There is a tendency for farmers to embody the land that they're farming and the conditions of their farm. I think a path that Jess spoke about is really kind of a diversified self. The challenge is to both embody the land, but also be separate enough to be able to continue to look from positioning ourselves perhaps above or beside or behind, as opposed to always within ourselves when we're looking at situations that we're facing. Through as many lenses that we can see ourselves, see what we do, see how we are existing within this whole changing, evolving system. Through that we can, we can usually find a kind of a sense of clarity. It's listening and observing and being quiet enough to have a sense of what a direction possibly is for how we can engage.

Martin Ping (25:17):

What is the role of our wider community and society in imagining a healthy farm and healthy farm economy and making this both the land and the good food accessible to more people?

Spencer Fenniman (25:29):

We're in this situation where we have farmers struggling to make ends meet and lots and lots of people struggling to put good food on their table. There's not an easy solution. The viability of local farms is essential towards providing people with more access to food, regardless of their income levels. CSA is really an opportunity where people can support both a farmer, but then also support their community and the broader access to food. When a farmer is supported by the community, the farmer then can turn around and do what they want to do, which is also in turn support the community. When commerce is limited to transactional commerce or commerce that's in a store exclusively and there isn't that deeper awareness of the relationship, there's less opportunity to really allow for farmers to provide the community and be supported by the community in return.

Martin Ping (26:26):

Hawthorne Valley has this mission statement of renewing soil, society, and self through the integration of agriculture, education, and art. And so I just want to end the conversation art and the creative process and where that fits in. I know I'm speaking to artists in one form or another. And I know if people who've been to Hawthorne Valley will easily be able to pick out beautiful murals of cows on the Creamery or painted birds flying on the side of the barn, grain silos with graffiti art on them. And I'm wondering if, is there a role for art on the farm? What would that be? How would you describe that?

Jess Brobst (27:13):

The process of being inspired and thinking and making decisions artistically and creatively is, I think, so necessary also as a farmer to look at the farm like a canvas, like what could come here and bring life to this corner of the farm, what could go there to bring beauty and vitality. To think in a creative way, you develop that as an artist, and can then use it as a farmer or probably anything, to think creatively and artistically, looking for beauty, looking for balance. Art is one of those words, kind of like, love. We take for granted how much power is behind that word. There's so much power behind love, but we kind of use that word without thinking about it. I think it's the same for art.

Spencer Fenniman (27:58):

I think of it too, as in providing space for kind of emergent properties. In a way the whole place here is an art installation, because I think in all those interactions and inner relationships is really one large artwork, manifested over time and space. I do think though, and specifically in, working with ecologists to allow for these emergent landscape properties to unfold in a tree that's allowed to grow, or a wildflower that's allowed to blossom is allowing for this creative process. I think in the same way, our cow horns. Allowing the cows to grow horns without management of those horns is really allowing this creative process of the cows being to be expressed. And I think that while that could lend itself beautifully to a piece of art, I think too, we are, in a way we're allowing the cows to unfold in this creative process in their own being. And there's a lot of spaces in this Association where that's being allowed as well, whether it's the Waldorf kids or in production practices into our yogurts. If we think of art as this creative process unfolding, I think that what we can always do is create more spaces and opportunities for it to unfold.

Martin Ping (29:24):

That just moved me so much what you shared and to think of Hawthorne Valley, possibly being that container for that emergence and that creative process in each of us. If we can support each other in that way, then it's worth all of the effort. I really can't thank you enough for your time and your wisdom. It's been so enlightening and enriching and inspiring. So Jess and Spencer, thank you both so much.

Heather Gibbons (30:07):

If you'd like to learn more about the farm, please visit our website at farm.hawthornevalley.org or better yet stop by our campus to experience it for yourself. Guided tours can be arranged through the farms website or stop into our store to pick up a self-guided tour brochure. While you're there, be sure to check out our full line of made on our farm products, including our Biodynamic and organic yogurt, cheese, raw milk, baked goods, animal welfare approved meat, our fermented veggie line, including our beloved sauerkraut and so much more. We are also thrilled to be offering Farmer Jess' very own creation, the 2022 Divine Bovine Calendar, featuring her artwork inspired by her interactions with the divine members of our dairy herd. This "cowlendar" is available at the Farm Store and all proceeds from the sale will benefit the Farm to help with improving areas where humans and cows interact.

Heather Gibbons (31:03):

Thanks for listening to Hawthorne Valley's Roots to Renewal podcast. We are an Association comprised of a variety of interconnected initiatives that work collectively to meet our mission. You can learn more about our work by visiting our website at hawthornevalley.org. Hawthorne Valley is a registered 501c3 nonprofit organization and we rely on the generosity of people like you to make our work a reality. Please consider making a donation to support us today. If you'd like to help us in other ways, please help spread the word about this podcast by sharing it with your friends and leaving us a rating and review. Special thanks to our sponsor Tierra Farm, who makes this podcast possible and to Grammy Award-winning artist, Aaron Dessner, for providing our soundtrack. Finally, we'd like to thank Aaron Ping for once again, lending his editing expertise.